12 Feb 2017

Why I love manufacturing: Or, how pickled onions changed my life.

At the age of eight, I found the perfect adventure playground - my grandad’s pickle factory. Defying all the health and safety regulations, even those few that existed in the 1970s, my younger brother and I made the factory into our personal play area. I remember, being allowed to ride on the fork lift with Walter the driver, climbing around four-high pallets of sacks of onions like a jungle gym and scaling ladders to look into the big tank of acetic acid in the roofspace that provided the vinegar for the whole factory. We had the run of the whole place and emboldened by the fact that our grandad was the boss, we made the most of our opportunities. I should add that the business was sold many years ago, the factory is closed and my grandfather is long dead, so I can make these confessions without fear of him being the victim of a 21st-century HSE SWAT team.

My grandfather apparently wanted to call the business APEX Pickles but some else had registered the name, so he just chose something that sounded similar. I have been back many times to see the building - it is pretty unassuming and seems much smaller than it did to an eight-year old. There was a greasy spoon café operating in the rooms that used to be the factory offices for a while and now a couple of engineering companies occupy the premises. It is an unlikely starting point for lifelong love affair, but it instilled in me a burning passion for manufacturing.

The factory of APX Pickles, was tucked in a little corner of Kirkstall in Leeds, not far from Kirkstall Abbey, butted up against the canal near Amen Corner bridge. I spent many hours by the edge of that canal, mainly catching slow-moving snails and leeches, with the odd stickleback, that I kept in an old water-filled pickle jar.

Maybe I just thought it was all great fun at the time, but wind the clock forward 15 years and it got serious when I was part of the commissioning team building the largest soft drinks factory in Europe. As the massive Coca-Cola factory rose out of the mud of a Wakefield brown-field site, I often thought back to my grandfather’s factory. He never got to see the Coca-Cola factory, but I think he would have approved

In the 1970s, machines for peeling onions efficiently, were not available, or so I was told by my grandfather. It might have been that he decided they were too expensive for his operation. The result was twenty women in two lines of ten, each side of a conveyor that supplied a constant stream of onions for peeling. The ladies worked so fast their hands were a blur; topping, tailing and peeling onions faster than the eye could keep up with and apparently without a single tear. They chatted constantly, peeling by some kind of sixth sense, hardly looking at their work as their knives slashed and cut.

I remember my embarrassment as they chorused ‘Here comes Johnny Reggae’ (a novelty song by The Piglets that charted in 1971, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nLaa77cP8-U ) very loudly at me as I went past. The ‘girls’ became almost part of the family, sharing the details of their lives with my grandparents and being helped out with a ‘sub’ on their wages on more than one occasion.

All that hand labour meant the factory was busy and active. It also needed feeding and at the prescribed time every day, everything stopped and everyone went off the canteen. Of course, that place was also part of my ‘industrial playground’. I remember being fascinated by a large chip-making hand machine, that was bolted to the work top and operated like a large garlic press, chopping potatoes into chips by the bucket load before transporting them to the industrial frier. And there was also a free supply of Blue Riband biscuits for the owner’s grandson!

That factory also gave me my first pay packet. By the age of ten or so, I was deemed old enough to be part of the process. I am pleased to say that I was not shredding hundreds of red cabbages in the very scary machine-of-a-100 blades, but folding up the carboard trays that were used to hold the pickles as they went into the plastic heat-shrink machine. I still remember the smell of melted plastic given off by the oven, which got a bit stronger ever time the heat control broke on the machine. I folded up the flat cardboard cut-outs into rounded trays and was paid 10p for every 100 trays that I made. It seemed like a fortune at the time and worth all the paper cuts on my fingers, but I am sure the kids of my age who would have gone up chimneys 100 years earlier, got paid better than I did!

I also learned an interesting way of dealing with customer complaints. In a factory that processes things into glass jars, it was almost inevitable that bits of glass would eventually get into a jar. Years later when I was supervising a bottling line in Aylesbury for Schweppes, it was a constant hazard and we still relied largely on the vigilance of the operator assigned to watch each washed bottle go past the inspection point. In those days, there was no easy way of being 100% certain there was no broken glass in a container. My grandad always dealt with customer complaints himself and to his credit he took them very seriously, personally delivering a case of free pickles to anyone who reported getting glass in their pickles. Of course, he had to take away the glass for ‘testing’ to see where it had come from, although I suspect this might have been more about removing the evidence in case of further action from the customer.

My Dad was Production Manager at the factory for a while, which seemed to involve mainly trying to fix broken machines and getting stained yellow with whatever terrible dye was used in piccalilli in those days. I remember him coming home, hands stained with red cabbage and washing them in neat bleach from under the sink, before sitting down to our family evening meal.

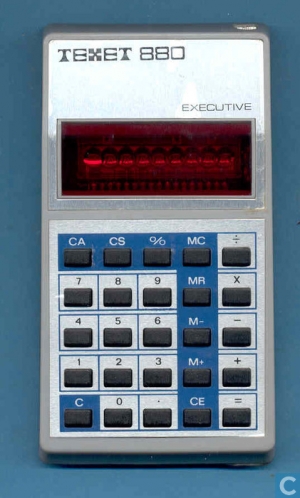

The other influence on my young life was that it was in the factory that I came across my first digital calculator. My grandmother did the accounts in the factory, and I had got used to the long ribbons of paper covered in numbers that spewed from the manual calculating machine that she used. (picture of old adding machine) However, one day I was introduced to my first electronic calculator a TEXET 880, that changed everything. The first office electronics I ever saw and (occasionally) had permission to use. What changes I have seen since those days.

As I approach my 30th anniversary of working in manufacturing, the excitement of making things in factories has stayed with me all my working life. The idea of bringing together so many independent parts, machines, people and throwing them into a mix to fashion some item that someone else is prepare to pay for, still gets my juices flowing. Managing stocks to make sure every little item that is needed to complete the product is available and ready to go. Making sure that people turn up when needed, that they are willing and able to do the tasks you ask of them. Ensuring that production can be planned to make sure the right things are in the right place at the right time. This still fires me up today and why I still love working with manufacturing companies best of all.